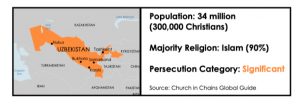

The doubly-landlocked country of Uzbekistan has the largest population in Central Asia and is ninety per cent desert and mountain, ranging from fertile valleys in the east to desert in the west. The Silk Road runs through the country, with the historic cities of Samarkand and Bukhara, known for their mosques and madrassahs, along its route.

The Uzbek people are considered to be the most religious in Central Asia and the government concentrates on keeping all religions (especially Islam) under strict control. The government appoints all imams and controls the number and location of mosques, and over two thousand Muslims are in prison for practising their faith without approval.

A former Soviet republic, Uzbekistan was ruled by the authoritarian Islam Karimov from 1989 until his death in 2016. When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991 he was elected president of the new country, and he was ruthless with all perceived opposition. His successor Shavkat Mirziyoyev won the presidential election with a landslide victory in December 2016 and his secular government made great strides in expanding religious freedom from 2018, with some churches granted registration and fewer police raids on church meetings, but progress stalled in 2021 with the introduction of a new Religion Law (see below) that retained the old law’s restrictions on meeting together, proselytism and religious literature.

While President Mirziyoyev’s rule has been described as an “Uzbek Spring” because he opened up Uzbekistan to international contacts, the state still violates many human rights and restricts freedoms of religion, speech, press and assembly.

Christians in Uzbekistan

Many Christians in Uzbekistan are of Russian ethnicity and most belong to the Russian Orthodox Church, which is recognised, but the house church movement has grown in recent years and there may be up to 10,000 ethnic Uzbek Christians. While a few Evangelical churches have been able to register in the last few years most have not and they often meet under secret service surveillance, risking police raids, fines and confiscation of literature. Converts from Islam also face pressure from family and community as they are seen as cultural or religious traitors.

All unregistered religious activity is illegal and incurs fines of up to three hundred times the minimum monthly wage and up to five years’ imprisonment. Unregistered religious groups cannot open bank accounts, appoint leaders, build, rent or buy buildings or print, distribute or import religious literature.

Christian literature (including Bibles) is routinely confiscated and destroyed. Christians have been told that it is legal to possess a Bible but that reading it is only allowed in designated areas such as registered church buildings. Only religious material approved by the State Committee for Religious Affairs may be distributed and while the government-recognised Uzbek Bible Society is allowed to exist it is heavily restricted and Bibles may not be sold through any other outlets. All imports of Bibles and Christian books are examined and sometimes confiscated and burnt and Christians accused of illegally storing, importing or distributing Christian materials can incur large fines.

Persecution is especially intense in Karakalpakstan, an autonomous republic that occupies the northwestern end of Uzbekistan. In its capital, Nukus, the church has been experiencing unprecedented growth, with several thousand people becoming Christians in recent years. The government shut every non-Orthodox church, so almost all growth is through underground house churches. In 2019, however, the first church was able to register in Karakalpakstan.

In 2017 the government publicly launched the first full Uzbek Bible (a translation of the Old Testament and a revision of the New Testament) at an event attended by ethnic Russian Christians only – Uzbek Christians were not invited.

Religion Law

Uzbekistan’s new Religion Law, which came into force in 2021, retains almost all the restrictions on freedom of religion and belief in the existing 1998 Law on Freedom of Conscience and Religious Organisations, which restricted rights deemed to be in conflict with national security.

These restrictions ban all exercise of freedom of religion and belief without state permission, teaching about religion without state permission and sharing beliefs. The new law retains the requirement for prior state censorship of all religious materials, whether printed or electronic. It also retains the burdensome registration process for religious communities, and while it reduces the number of adult citizens required to apply for permission for a religious community to exist from one hundred founders to fifty, it adds the requirement that all founders live in one city or district.

(Barnabas, Forum 18, Operation World, Religious Liberty Prayer Bulletin, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Annual Report 2013, Voice of the Martyrs Canada, World Watch list)

UZBEKISTAN: Easter Sunday raid on Baptist church

The church in Karshi has been raided on many occasions by police