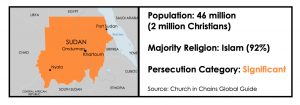

Sudan’s authoritarian president Omar al-Bashir was ousted in a military coup in 2019 after widespread protests calling for freedom and justice. Christians were severely persecuted under President Bashir but a new transitional government tasked with implementing comprehensive reforms brought positive changes, although Islamists protested against the reforms.

Sudan’s authoritarian president Omar al-Bashir was ousted in a military coup in 2019 after widespread protests calling for freedom and justice. Christians were severely persecuted under President Bashir but a new transitional government tasked with implementing comprehensive reforms brought positive changes, although Islamists protested against the reforms.

In 2020 the death penalty for apostasy was removed, Sudan became a secular state and amendments were passed that included the ending of public flogging and the banning of female genital mutilation, while new legislation permitted women to travel abroad with their children without proof of permission from a male guardian and allowed non-Muslims to import, drink and sell alcohol.

In October 2021, however, the military seized power in a coup that plunged the country into chaos and sparked fears that reforms would be reversed.

In April 2023 conflict broke out in Khartoum as a result of a power struggle between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and its former partner the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which was formed in 2013 and had its origins in the notorious Janjaweed militia. The SAF and the RSF had shared military rule following the coup but they disagreed over the direction of government, including the proposed move towards civilian rule, and conflict grew over plans to integrate the RSF into the army and who would lead the new force. Fighting soon spread across the country.

Since the start of the civil war tens of thousands of civilians have been killed and over thirty million are in need of humanitarian support, including medical and food aid. Over ten million people are internally displaced, while over three million more have fled the country and are classified as refugees.

Christians in Sudan

A campaign of Islamisation of Sudan intensified after South Sudan seceded in 2011, when President Bashir vowed to adopt strict Sharia and recognise only Islamic culture and the Arabic language. Harassment, arrests and persecution of Christians increased and the authorities expelled foreign Christians and demolished or confiscated church buildings on the pretext that they belonged to South Sudanese Christians, whom they threatened to kill if they did not leave or cooperate with efforts to find other Christians.

In April 2013, the government announced that no new licences would be granted for church buildings, claiming that a decrease in the South Sudanese population would make them unnecessary.

In 2019, following the ousting of President Bashir, senior government officials showed support for Christians by attending church services in Khartoum on Christmas Day and the government-run Sudan TV broadcast Christmas services from several churches. This followed the government’s announcement of Christmas as a public holiday for the first time since its suspension following the secession of South Sudan.

At a press conference after visiting several Khartoum churches on Christmas Day, Sudan’s new Minister of Religious Affairs and Endowments, Nasr al-Din Mufreh, acknowledged that Christians had faced persecution during the previous regime, stating: “I tender my apology for the oppression and the harm inflicted on you physically, by destruction of your temples, the theft of your property and the unjust arrest and prosecution your servants and confiscation of church buildings.” He later said that property stolen from Christians would be returned.

Despite the transitional government’s reforms, however, Christians remain at risk of persecution, particularly converts from Islam, including severe pressure from extended family, community and religious leaders, denial of inheritance, violent attacks, forced marriage and rape.

Since fighting broke out between the SAF and the RSF, many Christians have been forced to flee their homes and are struggling to survive. In June 2024 Sat-7 UK reported that since the fighting began over 165 church buildings had been damaged or destroyed, with both sides in the conflict targeting them. Some church buildings have been looted and turned into military bases.

Under attack in the Nuba Mountains

Christians have come under severe attack in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan, on the border with South Sudan. The region has a significant black, ethnic Nuba Christian population, which government forces targeted for many years in a brutal campaign of aerial bombardment aimed at quashing rebels (the Sudan People’s Liberation Army) and ridding the region of non-Arabs and Christianity and making it solely Arabic and Islamic. The bombardment destroyed homes, churches, schools and hospitals, and starvation tactics destroyed crops and livestock. Thousands of Nuba fled to refugee camps in South Sudan and Human Rights Watch described the operation as ethnic cleansing.

Background

Sudan gained independence from joint British/Egyptian rule in 1956 and civil war broke out as the mainly Christian, Animist and African south struggled against economic, political and social domination by the Arab Muslim north.

The war became even more brutal when vast oil reserves were discovered in southern Sudan and anti-Christian persecution grew. Islamist militias bombed churches, murdered Christians, destroyed villages, hospitals, schools and missions, and abducted women and children into slavery.

War ended with the signing of the north-south Comprehensive Peace Accord in 2005, leading to South Sudan’s secession in 2011. The decades of conflict had led to the deaths of an estimated two million people and the displacement of four million people.

(Asharq Al-Awsat, Barnabas, BBC, Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Guardian, International Christian Concern, International Organisation for Migration, Morning Star News, UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Release International, Religious Liberty Prayer Bulletin, Sat-7 UK Sudan Briefing June 2024, Voice of the Martyrs Canada, World Watch List)

SUDAN: Convert couple finds safety in USA

Nada and Hamouda faced the threat of death after being accused of apostasy

SUDAN: Four Christians shot dead

A pastor and three other Christians have been shot dead by suspected Islamic extremists

SUDAN: Pastor arrested after praying for healing

A Sudanese pastor has been arrested and jailed after leading a prayer meeting for his sick mother

SUDAN: Baptist couple may face flogging for “adultery”

A Baptist couple from Gezira state could face flogging after being charged with “adultery”

SUDAN: Prosecutor dismisses apostasy case

The General Prosecutor in Central Darfur state has dismissed a case against four Baptists who were charged with apostasy